Environmental Factors

Summary

Environmental factors were linked to cancer in 1977 (1). A World Health Organization (WHO) review regarding environmental risk factors for cancer in 2019 reported that 35% of worldwide cancer deaths are due to risk factors resulting from lifestyle choices (2). Factors can be broken down into three categories: physical, chemical, and biological.

The most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States is skin cancer. Studies have shown that excessive exposure to ultraviolet light/ radiation increases the risk of skin cancers such as melanoma and squamous skin carcinoma. Some individuals theorize that ultraviolet light will kill “cancer causing microbes” in the bloodstream, therefore leading to a fully functional immune system. Although ultraviolet radiation/light has a well-known antiviral effect on surfaces, Studies have shown that many people believe Ultraviolet Blood Irradiation therapy must act by killing pathogens in the bloodstream. However there is no evidence that this is the case (3).

Menna Elsaka

Undergraduate from Lamar University

It has been proven to cause damage to DNA, as well as the pathways that lead to apoptosis (programmed cell death), The result of this damage is that cells lose the ability to control their proliferation, resulting in an “immortal state,” with increased proliferation of these damaged and immature cells, which is a hallmark of cancer progression (2). All of these factors, backed by scientific evidence, give credence to the fact that UV light will not kill microbes in the bloodstream. It is also important to note that these ‘microbes’ in the bloodstream do not cause cancer but rather the inflammation left behind due to toxins or infections.

Tobacco and alcohol use are among the highest risk factors for pancreatic cancer. There is a strong scientific association between alcohol consumption and several types of cancers, including breast, liver, upper respiratory/digestive tract, pancreas and colon. Studies have linked the immunosuppressive effects of alcohol with tumor progression and metastasis (4). Similarly, there is an association between smoking and developing lung cancer. Smokers are 6 to 10 times more likely to develop lung cancer than nonsmokers.

Dietary factors also have been linked to cancer. The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) reported that 35 % of cancer incidences can be connected to nutrition and lack of physical activity. In 2018, an epidemiological study reported that physical exercise can reduce the risk of at least 13 different types of cancer (5). Evidence from the study suggested that exercising can reduce tumor incidence, tumor growth, and metastasis across a wide range of tumor models (5).

There are risk factors in the global population that can not be fully controlled, such as industrialization. However, other risk factors can be avoided by altering one’s lifestyle.

References

- Parsa N. (2012). Environmental factors inducing human cancers. Iranian journal of public health, 41(11), 1–9. (history)

- Lewandowska, A. M., Rudzki, M., Rudzki, S., Lewandowski, T., & Laskowska, B. (2019). Environmental risk factors for cancer – review paper. Annals of agricultural and environmental medicine : AAEM, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/94299

- Hamblin M. R. (2017). Ultraviolet Irradiation of Blood: “The Cure That Time Forgot”?. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 996, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56017-5_25

- Ratna, A., & Mandrekar, P. (2017). Alcohol and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapies. Biomolecules, 7(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom7030061

- Hojman, P., Gehl, J., Christensen, J. F., & Pedersen, B. K. (2018). Molecular Mechanisms Linking Exercise to Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Cell metabolism, 27(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.015

Full Article

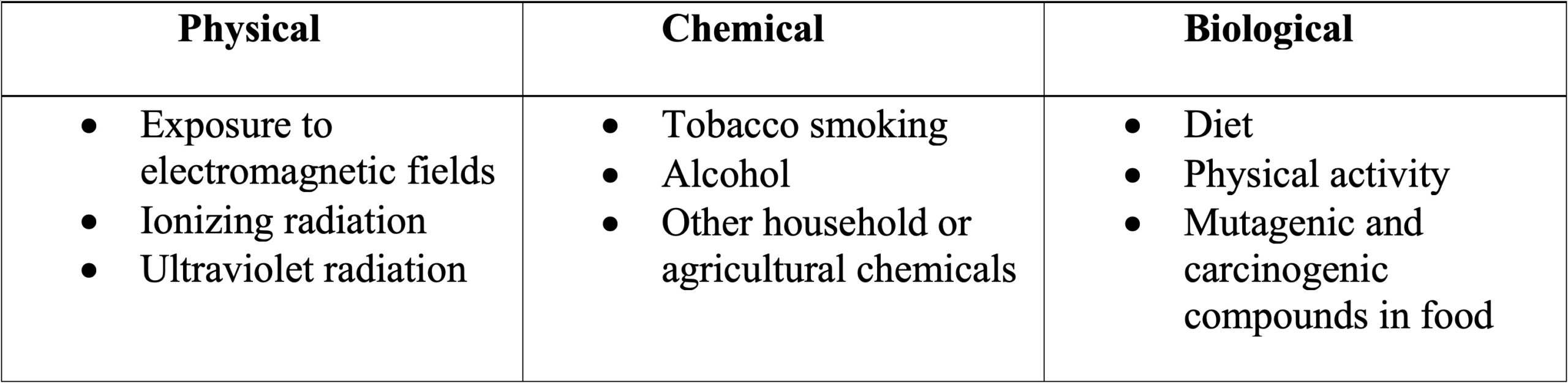

Environmental factors were linked to cancer in 1977 (1). It was first noticed in the workplace due to workers in certain occupations being exposed to particular chemicals for longer periods of time than the general population (2). In 2019, a World Health Organization (WHO) review regarding environmental risk factors for cancer reported that 35% of worldwide cancer deaths are due to risk factors resulting from lifestyle choices (3). Factors can be broken down into three categories: physical, chemical, and biological. The table below shows some examples for each category:

In 1998, The WHO considered exposure to a magnetic field of 50/60 Hz a probable factor in tumor initiation. Epidemiological studies performed in 1979 proved that there is an increased risk of leukemia among American children who are living in homes with higher than average intensity of magnetic fields. In Sweden, another study showed that women living within a radius of 300 meters from power lines had doubled their relative risk of developing breast cancer by being exposed to low frequency magnetic field (0-300 Hz). Similarly, high exposures to chemical factors such as pesticides, smoke, hair dye, as well as agricultural chemistry may increase the risk of developing cancer (3).

Literature reports a 2-3% chance that radiation exposure will cause cancer in exposed individuals. When higher doses of radiation are needed in procedures such as brain tumor therapy, there is an increased risk of developing additional gliomas and glial tumors. Women with malignant tumors in the chest undergoing radiation therapy are more likely to develop breast cancer. Research demonstrates that the risk of breast cancer begins to increase about eight years after exposure to radiation (3).

The most common environmental factor that affects the skin is ultraviolet radiation. Excessive exposure to sunlight often leads to sunburns, erythema (redness of skin) and even late symptoms of accelerated skin aging. Studies have shown that excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation increases the risk of skin cancers such as melanoma and squamous skin carcinoma. In 2009, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified the radiation emitted by solarium lamps as a carcinogenic factor in the context of skin cancers.

Some individuals theorize that ultraviolet light will kill “cancer causing microbes” in the bloodstream, therefore leading to a fully functional immune system. Although ultraviolet radiation has a well-known antiviral effect on surfaces, studies have shown that many people believe Ultraviolet Blood Irradiation therapy must act by killing pathogens in the bloodstream. However, there is no evidence that this is the case (4). It has been proven to cause damage to DNA, as well as the pathways that lead to apoptosis (programmed cell death). The result of this damage is that cells lose the ability to control their proliferation, resulting in an “immortal state,” with increased proliferation of these damaged and immature cells, which is a hallmark of cancer progression (3). All of these factors, backed by scientific evidence, give credence to the fact that UV light will not kill microbes in the bloodstream. It is also important to note that these ‘microbes’ in the bloodstream do not cause cancer but rather the inflammation left behind due to toxins or infections.

Tobacco and alcohol use are among the highest risk factors for pancreatic cancer. There was a study performed on healthy rats were they were exposed to daily cigarette smoke for four months, as a result they exhibited precursors to pancreatic cancer such as: acinar cell loss (acinar cells are secreting cell lining), increased pancreatic matrix deposition and infiltration of the pancreas with CD45- positive immune cells which is crucial for proper B and T cell function (5). Similarly, there is a strong scientific association between alcohol consumption and several types of cancers, including breast, liver, upper respiratory/digestive tract, pancreas and colon. Studies have linked the immunosuppressive effects of alcohol with tumor progression and metastasis (6).

Dietary factors also have been linked to cancer. In early studies, researchers estimated from the epidemiological evidence that more than 90 % of gastrointestinal cancers were diet-driven (7). In 2002, a monograph presented by the IARC showed evidence correlating overweight and obesity as the cause of esophagus, endometrium, kidney, colon and breast cancer. A few years later in 2007, the WCRF confirmed the evidence and also declared that there is a direct link between obesity and development of rectal, pancreatic, and gallbladder cancer (3). In 2012, colorectal cancers represented nearly 10% of worldwide cancer cases (7). Incorrect diet is considered one of main causes of malignant tumors. In 2007, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) reported that 35 % of cancer incidences can be connected to nutrition and lack of physical activity. All studies were gathered from a review article published recently in 2019.

Some dietary factors indicated by the WCRF to have a direct effect on cancer progression are: consumption of red and processed meat, insufficient intake of non-starchy vegetables, dietary fiber and excessive intake of salt. Other risk factors may include deficiencies of iron, folic acid, and vitamins, especially vitamin A (3). In 2018, an epidemiological study reported that physical exercise can reduce the risk of at least 13 different types of cancer (8). Evidence from the study suggested that exercising can reduce tumor incidence, tumor growth, and metastasis across a wide range of tumor models (8). Exercise has been proposed to target and improve almost every outcome in cancer patients and it is generally associated with positive changes in physiological measurements (8).

There is a point where reversing the physical damage to organs/organ systems caused by an environmental factor is possible. For some people, it depends on early detection or at what stage a diagnosis was given. For example, some gastric cancer cases can be divided into early and advanced stage gastric cancer (9). Early-stage disease can be detected by diagnostic testing which will analyze the submucosa (a thin layer of tissues found in the gastrointestinal tract (9). Advanced gastric cancers include advanced tumors which will determine the treatment strategies and overall prognosis (9). Patients who get diagnosed with early-stage disease can undergo radical surgery followed by chemotherapy. The post-operative 5-year survival rate is 90%. However, since the symptoms are hard to detect and the diagnosis rate is low, most patients are diagnosed with advanced stage disease. Unfortunately, at this point, advanced tumor cells have developed a decreased sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs and surgery is often not an option (9).

Similarly, with respect to pancreatic cancer, only a minority of patients can improve their pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) case with surgery (10). However, unlike gastric cancer, prevention for pancreatic cancer has been elusive and requires further research. Currently, immunotherapies have shown some promise, but no true clinical benefits in pancreatic cancer prevention(11). There are ongoing efforts to develop effective treatment options such as a preventative vaccine against pancreatic cancer (11).

Lung cancer is also similar to gastric and pancreatic cancers as patients are diagnosed so late that approximately two-thirds of patients miss the opportunity for surgical treatments (12). Smokers are 6 to 10 times more likely to develop lung cancer than nonsmokers. Second hand smoke accounts for a 30% to 60% increase in the risk for lung cancer development (12). Education and awareness regarding these risks is used as a method of prevention. Early diagnosis is preferable to high-risk individuals and can be made by analyzing chest x-rays, sputum tests, and bronchoscopies (12). One study classified current smokers, individuals who are exposed to second hand smoke or individuals who had quit smoking within the last 15 years as high-risk patients (13).

Early detection can be crucial when it comes to skin cancer as well. As mentioned before, skin cancer is largely preventable and is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States as of 2018 (14). Dermoscopic screening, which is an examination of the skin using a microscope, has allowed for earlier detection of melanomas (15). Dermoscopy has also been used to detect keratinocyte carcinomas. Early detection can lead to timely initiation of therapies and therefore improve patient outcomes (14). Other preventative efforts include increasing awareness about the dangers of UV exposure, the use of sun protection, and promoting screening tests particularly to those who are high-risk patients. The use of nicotinamide, which is a form of Vitamin B3, has demonstrated efficacy in the prevention on nonmelanoma skin cancer (14).

There are risk factors in the global population that can not be fully controlled, such as industrialization. However, other risk factors can be avoided by altering one’s lifestyle. No treatment or lifestyle is guaranteed to keep a person cancer free. Positive changes including modified lifestyle choices are advisable to avoid risks that have been scientifically proven to increase a person’s chance of developing cancer. Living in today’s world where the risk of developing cancer is fairly high could be compared to living in a house (body) with poor water pipes (internal and external cancer risk factors). In this scenario, the chances of these pipes breaking and flooding the house is high. However, if the individual is diligent and gets an inspection (medical evaluation), many problems can be avoided before escalation occurs. The unfortunate scenario is that far too many individuals live carelessly, knowingly exposing themselves to environmental risk factors that can be avoided, similar to leaving all the faucets open and flooding the house themselves.

References

- Parsa N. (2012). Environmental factors inducing human cancers. Iranian journal of public health, 41(11), 1–9. (history)

- U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2003, August). Cancer and the environment. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/materials/cancer_and_the_environment_508.pdf

- Lewandowska, A. M., Rudzki, M., Rudzki, S., Lewandowski, T., & Laskowska, B. (2019). Environmental risk factors for cancer – review paper. Annals of agricultural and environmental medicine : AAEM, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/94299

- Hamblin M. R. (2017). Ultraviolet Irradiation of Blood: “The Cure That Time Forgot”?. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 996, 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56017-5_25

- Korc, M., Jeon, C. Y., Edderkaoui, M., Pandol, S. J., Petrov, M. S., & Consortium for the Study of Chronic Pancreatitis, Diabetes, and Pancreatic Cancer (CPDPC) (2017). Tobacco and alcohol as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology, 31(5), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.001

- Ratna, A., & Mandrekar, P. (2017). Alcohol and Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapies. Biomolecules, 7(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom7030061

- O’Keefe S. J. (2016). Diet, microorganisms and their metabolites, and colon cancer. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 13(12), 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.165

- Hojman, P., Gehl, J., Christensen, J. F., & Pedersen, B. K. (2018). Molecular Mechanisms Linking Exercise to Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Cell metabolism, 27(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.015

- Song, Z., Wu, Y., Yang, J., Yang, D., & Fang, X. (2017). Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumor Biology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010428317714626

- Singhi, A. D., Koay, E. J., Chari, S. T., & Maitra, A. (2019). Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges. Gastroenterology, 156(7), 2024–2040. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.259

- Morrison, A. H., Byrne, K. T., & Vonderheide, R. H. (2018). Immunotherapy and Prevention of Pancreatic Cancer. Trends in cancer, 4(6), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2018.04.001

- Hong, Q. Y., Wu, G. M., Qian, G. S., Hu, C. P., Zhou, J. Y., Chen, L. A., Li, W. M., Li, S. Y., Wang, K., Wang, Q., Zhang, X. J., Li, J., Gong, X., Bai, C. X., & Lung Cancer Group of Chinese Thoracic Society; Chinese Alliance Against Lung Cancer (2015). Prevention and management of lung cancer in China. Cancer, 121 Suppl 17, 3080–3088. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29584

- Hoffman, R. M., & Sanchez, R. (2017). Lung Cancer Screening. The Medical clinics of North America, 101(4), 769–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.03.008

- Lopez, A. T., Carvajal, R. D., & Geskin, L. (2018). Secondary Prevention Strategies for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.), 32(4), 195–200.

- Wolner, Z. J., Yélamos, O., Liopyris, K., Rogers, T., Marchetti, M. A., & Marghoob, A. A. (2017). Enhancing Skin Cancer Diagnosis with Dermoscopy. Dermatologic clinics, 35(4), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2017.06.003